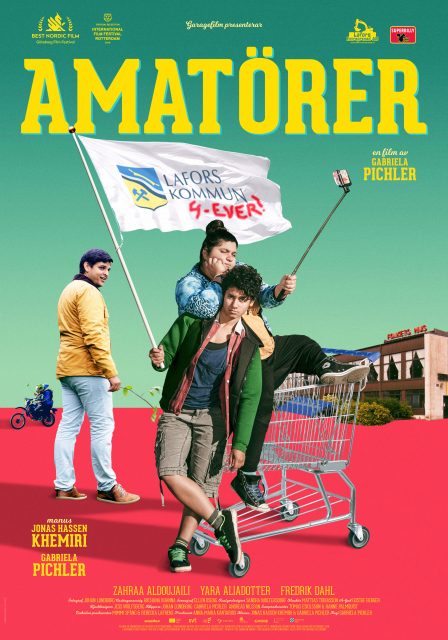

Writing Workshop For Undocumented

In the spring of 2013, Khemiri started a writing workshop for people who are living or have experienced living as undocumented migrants in Sweden. Dremko Candil, who participated in the workshop, wrote this beautiful piece, published in Swedish by Aftonbladet, Norwegian by Klassekampen and English by the literary journal Asymptote. The writing workshop ended in 2014.

Introduction by Jonas Hassen Khemiri

In spring 2013, we organised our first writers’ workshop for undocumented migrants. The journal Artikel 14, covering issues of refugee and migration policy, set up a web page, a secret location, and coffee. The organisation No one is illegal invited the participants. I was responsible for the actual activities and content. At each meeting we read a short text, typically a short story or an extract from a novel. We tried to understand the text, analysed it, examined why it fascinated/bored, why we felt like framing/burning it. After that, we tried to mimic it, and wrote something that resembled that text. Or, perhaps, wrote something that was the complete opposite. Participating in the workshop was free of charge, the only prerequisite that the participants should be, or have some experience of being, undocumented in Sweden.

The primary challenge was linguistic. How to communicate in a room with so many mother tongues? The strategy was to use English as the main spoken language and use the participants’ respective mother tongues in writing. Where necessary, the English was simultaneously interpreted into Farsi and Spanish. When that didn’t help, or didn’t help enough, we turned to the whiteboard, sign language, and charades.

The text published here, and in Aftonbladet, was written after a session where we were inspired by the artist Joe Brainard’s I Remember, a memoir based on short mementos—in no chronological order. Every new line begins with a hypnotic refrain, the same words, over and over again: I remember. . . Jag minns. Je me souviens. Yo me acuerdo.

The act of remembering, the act of recording, the importance of bearing witness, to have a voice despite uncertainties regarding one’s legal status, to have access to words despite being undocumented, to never let someone else speak for me, to never let the dehumanising words of Power stick to you. Here are Dremko’s memories.